“Leonardo’s Last Supper is one of the most famous pictures in the world—rivaled only by Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam and Edvard Munch’s The Scream… Like other supericonic images it has been reproduced, appropriated, plagiarized, and lampooned to such a degree that it is very difficult to think of it soberly in its functional context. We are confronted by what everyone can see is a very battered image, high on one of the end walls of a large hall… We are in the presence of a certified masterpiece; that is what matters.”

— Martin Kemp (born 1942), British art historian, exhibition curator and author of Leonardo By Leonardo (2019). [1]

The Last Supper Museum requires that tickets be purchased months in advance. As part of the ticket package, I joined a guide-led walking tour that met at the Milan Cathedral and visited various other landmarks, including Sforza Castle. Duke Ludovico Sforza (1452-1508) held court at the fortification, where he employed various artists, including da Vinci, who in 1482 began working for the nobleman for roughly 18 years. The final stop on our tour was at this building, Santa Maria delle Grazie, the site of da Vinci’s masterwork. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

“When you have been well-schooled in [linear] perspective and have committed to memory all the parts and forms of things, let it please you often when you are out walking to observe and contemplate the positions and actions of men in talking, quarreling, laughing and fighting together—what actions there might be among them, among the bystanders, those who intervene or look on. Record these with rapid notations in this manner in a little notebook which you should always carry with you.”

— Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), painter, sculptor, architect, scientist, anatomist, geologist, engineer, inventor, theatrical designer and musician, writing in his posthumously published treatise on painting. [2]

En route to view the mural, our guide led our group through the church’s Gothic nave. The main sections of the convent were built by 1469 and the nave by 1482. Sforza commissioned and funded the construction of the church and he intended to use it as a mausoleum for his family. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

On exiting the church, our tour group waited for several minutes outside the refectory that is now a museum. Sforza commissioned da Vinci to paint the Last Supper on a wall in the refectory where the Dominican monks dined and observed Christ sharing a final meal with his disciples. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

“That figure is most praiseworthy which best expresses through its actions the passion of its mind… The motions and postures of figures should display the true mental state of the originator of these motions, in such a way that they could not signify anything else... Vary the air of faces according to the states of man—in labor, at rest, enraged, weeping, laughing, shouting, fearful, and suchlike.”

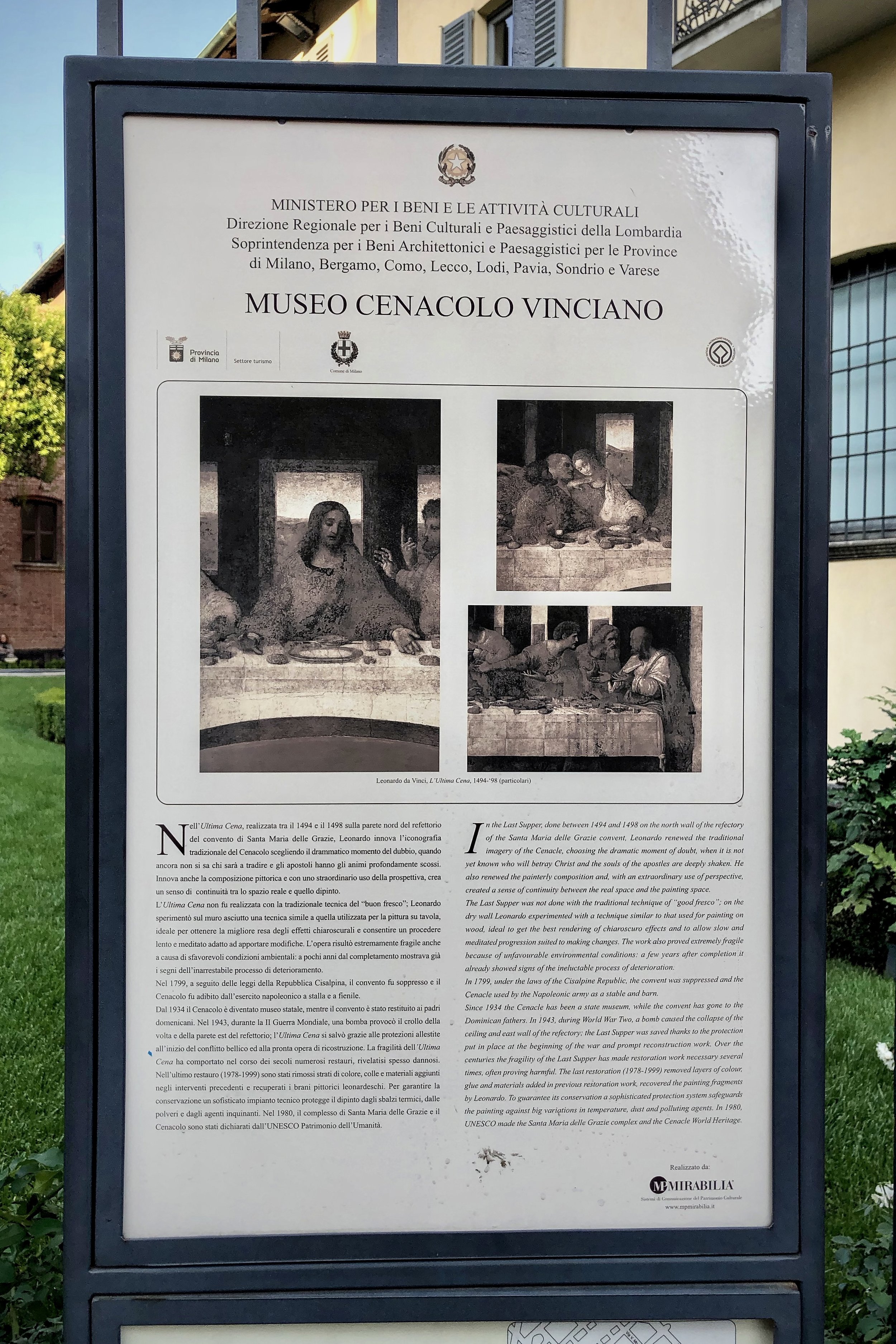

Several informational signs (in Italian and English) about the church-convent and mural are posted outside. This sign next to the refectory-turned-museum notes that the ever-experimental da Vinci used a technique in paints and a solution on the Last Supper that unfortunately failed, due partly to the building’s poor climate conditions. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

“One who was drinking has left his glass in its place and turned his head towards the speaker.

“Another wrings the fingers of his hands and turns with a frown to his companion.

“Another with hands spread open to show the palms shrugs his shoulders up to his ears and mouths astonishments.

“Another speaks in his neighbor’s ear, and the listener twists his body round to him and lends his ear while holding a knife in one hand and in the other some bread half cut through by a knife.

“Another while turning round with a knife in his hand upsets a glass over the table with that hand.

“Another places his hands upon the table and stares.

“Another splutters over his food.

“Another leans forward to see the speaker and shades his eyes with his hand. Another draws back behind the one who inclines forward and has sight of the speaker between the wall and the leaning man.”

— da Vinci, writing in a pocket notebook his observations of people sitting at a table. [3]

When our tour guide finally opened the sliding door into the climate-controlled refectory, I was struck by how colorful the painting appeared, given its centuries-long deterioration and some ill-advised re-paintings and restorations. Later, I realized the lights in the long, large room were positioned to maximize its overall tone.

At last, I was viewing my hero’s masterpiece in the flesh and felt a mix of accomplishment, delight and wonder. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

“Many a time I have seen Leonardo go to work early in the morning and climb on to the scaffolding, because the Last Supper is somewhat above ground level; and he would work there from sunrise until the dusk of evening, never laying down the brush, but continuing to paint without remembering to eat or drink. Then there would be two, three or four days without his touching the work, yet each day he would spend one or two hours just looking, considering and examining it, criticizing the figures to himself. I have also seen him (when the caprice or whim took him) at midday when the sun is highest leave the Corte Vecchia, where he was working on the stupendous Horse of clay, and go straight to the Grazie; climbing on the scaffolding, he would pick up a brush and give one or two brushstrokes to one of the figures, and then go elsewhere.”

“[A]lthough most excellent, it [the Last Supper] is beginning to deteriorate, I do not know whether it is because of the humidity that the wall produces or because of another inadvertent problem.”

— Antonio de Beatis (15th-16th centuries), secretary to Cardinal Luigi d'Aragona, on viewing the Last Supper in 1517. [6]

Once inside the refectory, each tour group (of 30 people maximum) is permitted just 15 minutes to view the majestic painting. With my Nikon D90 camera in hand, I was dismayed to find the room was dimly lit and its windows sealed to block any natural illumination. My weakness as a photographer is shooting in low light.

Hence, my initial photos of the mural were too underexposed to salvage. Rather than waste precious time wrestling with my camera’s settings, I pivoted to my trusty iPhone camera. Thankfully, I captured a few decent shots.

Although, when checking my photos after leaving the museum, my heart sank. The apostle Simon (far right) appeared faceless! I assumed all of my photos had suffered similarly. I later realized that Simon’s features had deteriorated beyond recognition on the wall. (Photo: Maureen Jones)

“King Louis of France is said to have been so taken with this work that, contemplating it with profound emotion, he asked those around him whether it was possible to remove it from the wall and take it back to France, even if it meant destroying the famous refectory.”

— Paolo Giovio (1483-1552), Italian physician, historian and biographer. [7]

“This work, left in this final state, is perpetually held in great veneration by the Milanese, and also by visitors from outside, in that Leonardo has imagined and managed to realize the suspicions that assailed the Apostles about who was to betray their master. ”

“This picture is the foremost in the world and the masterpiece of all painting.”

— Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758-1823), French painter. [9]

The dining hall was gradually turned into a museum during the 19th century. “The idea of a Last Supper Museum began to develop; open daily to the public…” reads one of several signs outside the hall’s exit door. The early museum once housed new and earlier copies of da Vinci’s masterwork, as seen in the sign’s image circa 1895. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

Through the centuries, several attempts were made to restore or conserve the mural that began deteriorating during da Vinci’s lifetime. This sign features painter and restorer Luigi Cavenaghi reworking the masterpiece in 1908. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

“In Leonardo da Vinci’s painting, artistic skill reigns free, having developed enough to attempt the most difficult task. The Lord’s words, the prediction that someone at the table would betray him, agitates the whole group with great suddenness and vehemence. All are startled and form highly animated, superbly arranged groups. There is life and movement everywhere. The diversity of emotions and gestures could not be greater. The pose, figure and features of each person reflect perfectly what he has heard and the pain he feels; the rendering is true-to-life and strong. … Probably no other examples could demonstrate so clearly and vividly the beginning stages and later perfection of the art of early modern times.”

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1758-1823), German poet, playwright and critic. [10]

When I read Walter Isaacson’s 2017 biography Leonardo da Vinci, it rekindled my youthful fascination with the Renaissance polymath and spurred me on to Italy to finally view his Last Supper.

A highlight of the book is Isaacson’s insightful description of how the apostles respond to Christ’s pronouncement that one among them will betray him: their emotional reactions unfold across time, from left to right.

The trio at the far left of the table are all, Isaacson observes, “still showing the immediate reaction” with Bartholomew, farthest left, “in the process of leaping to his feet, ‘about to rise, his head forward,’ as Leonardo wrote,” while Andrew, third from left, throws up his hands in surprise.

Conversely, the gesticulative group at the other end of the table, Matthew, Thaddeus and Simon, “are already in a heated discussion about what Jesus may have meant,” Isaacson writes. [11] (Photos: Joseph Kellard)

“Through the mists of repaint and decay... we can appreciate some of the qualities which made the ‘Last Supper’ the keystone of European art. We can recognize Leonardo’s power of invention by the simple means of comparing his treatment of the subject with any other which had preceded it. The Last Suppers of Ghirlandaio and Perugino, painted only a year or two earlier, show fundamentally the same composition as that which had satisfied the faithful for almost a thousand years.”

With the threat of Allied Bombers looming over Milan in 1943, the church piled sandbags within a braced scaffolding to protect the iconic mural from further damage or destruction. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

“One must visualize what it was like when the painting was uncovered, and when, side by side with the long tables of the monks [for whom it was painted], there appeared the table of Christ and his apostles. Never before had the sacred episode appeared so close and so lifelike. It was as if another hall had been added to theirs, in which the Last Supper had assumed tangible form.”

— E.H. Gombrich (1909-2001), Austrian-British art historian and author of The Story of Art (1950). [13]

An Allied bomb struck some 30 yards from the refectory on August 15, 1943, destroying its roof, vaults and eastern wall. Yet the Last Supper and a fresco on the wall opposite from it, The Crucifixion by Donato Montorfano, survived relatively unscathed, with fragmentary paint and priming disposed from the former. This sign shows an image of Santa Maria delle Grazie during reconstruction. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

“Never again, so profoundly, has an artist revealed in one picture so many souls…”

— Will Durant (1885-1981), American historian and author of The Story of Civilization (1935–1975). [14]

What originally inspired me to want to travel to Italy to view the Last Supper? At 19, I had already been fascinated with da Vinci when I read a 1985 New York Times Magazine feature about an ongoing project to conserve his masterwork, led by art restorer Pinin Brambilla Barcilon. Ultimately, the project took 22 years to complete, from 1977 to 1999. Restorers estimate that just 20 percent of da Vinci’s original paints remain. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

In retrospect, I probably first learned about art restorations from that Times article. That heightened my sense of the Last Supper’s significance in Western art, one highly worthy of such extensive care. These passages that I underlined when I first read the article also indicate what inspired my vow to one day visit the world-famous mural. Here are other passages I underlined:

* “Perhaps no other work of art, with the possible exception of Leonardo’s ‘Mona Lisa,’ has provoked so many books, articles, poems and lectures—and disputes—among scholars.”

* “Dr. Brambilla, the Milanese restorer, uses several solvents designed to work against non-Leonardo materials. Where nothing of the original remains, she lays in an easily removed neutral watercolor. It’s a slow process. She averages each day an area the size of postage stamps on the 420-square-foot mural. At this rate, without unforeseen troubles, she will need perhaps five more years to complete a labor begun in 1977.”

* “‘They always say the figure of Christ was never finished, or left half-finished,’ she says. ‘It’s not true. Leonardo did finish it as he did everyone else here.’” [16] (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

“The result is the most spellbinding narrative painting in history, displaying multiple elements of Leonardo’s brilliance... By conveying ripples of motions and emotions, Leonardo was able not merely to capture a moment but to stage a drama, as if he were choreographing a theatrical performance. The Last Supper’s artificial staging, exaggerated movements, tricks of perspective, and theatricality of hand gestures demonstrate the influence of Leonardo’s work as a court impresario and producer.”

— Walter Isaacson (born 1952), American journalist, professor, biographer and author of Leonardo da Vinci (2017). [15]

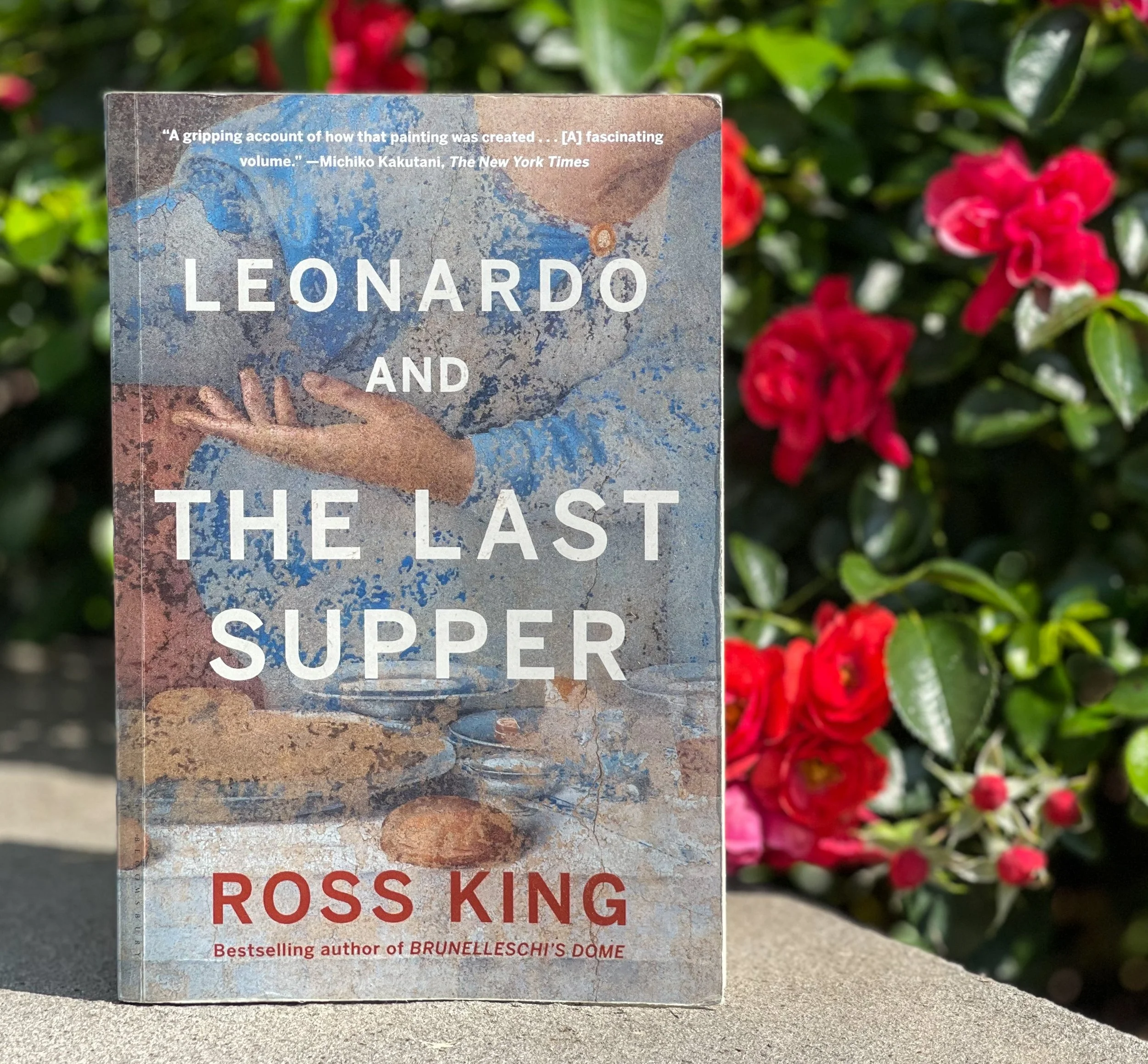

While in Italy, I was able to view four other da Vinci paintings in Milan and Florence. When I returned home to New York, I was inspired to read many books about the Renaissance man, including this excellent 2012 publication on the making of the masterpiece. (Photo: Joseph Kellard)

“The Last Supper is indeed a landmark in painting. Art historians identify it as the beginning of the period they used to call the High Renaissance: the era in which artists such as Michelangelo and Raphael worked in magnificent and intellectually sophisticated style emphasizing harmony, proportion, and movement. Leonardo had effected a quantum shift in art, a deluge that swept all before it.”

— Ross King (born 1962), Canadian novelist and author of Leonardo and The Last Supper (2012). [17]

“It’s hard for us today, given the number of copies that exist, given the influence that it’s had, to really understand how radical it was in the period itself. It was radical in the way it was painted, using highly experimental and unfortunately not very good techniques, in terms of its long-term survival. It was radical in terms of the way that the apostles and Christ interact. It was radical in the facial features that were pictured, in the gestures, in the astonishing interactivity of all of those characters. And now we can only get a hint of just how beautiful it must have once been. ”

References

1. Martin Kemp, Leonardo By Leonardo, (New York: Callaway, 2019) p. 94.

2. Martin Kemp and Margaret Walker, Leonardo On Painting, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989), p. 199.

3. Martin Kemp and Margaret Walker, Leonardo On Painting, pp. 227-228.

4. Martin Kemp and Margaret Walker, Leonardo On Painting, pp. 144-146.

5. Martin Kemp, The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 166.

6. Carmen Bambach, Leonardo da Vinci: Master Draftsman, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003), p. 239.

7. Frank Zollner, Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings, (Los Angeles: Taschen, 2011), p. 122.

8. Martin Kemp and Lucy Russell (translators), The Life of Leonardo by Giorgio Vasari, (London and New York: Thames & Hudson, 2019 ), p. 82.

9. Frank Zollner, Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings, (Los Angeles: Taschen, 2011), p. 135.

10. John Gearey, “Goethe: Essays on Art and Literature,” (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994) pp. 60-61. (Originally published by Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag.)

11. Walter Isaacson, Leonardo da Vinci, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), pp. 283-284.

12. Kenneth Clark, Leonardo da Vinci, (London: Penguin Books, 1993), p. 149.

13. Ernst Gombrich, The Story of Art, (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 16th Edition, 1995), p. 296.

14. Will Durant—Leonardo da Vinci (16:58 mark). (Originally from Will Durant, The Story of Civilization: Book V: The Renaissance, 1953.)

15. Walter Isaacson, Leonardo da Vinci, pp. 280-281.

16. Curtis Bill Pepper, “Saving ‘The Last Supper,’” (The New York Times Magazine, October 13, 1985.)

17. Ross King, Leonardo and The Last Supper, (New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2012), p. 268.

18. Leonardo: The Works, “One of You Will Betray Me” (United Kingdom: Seventh Art Productions, 2019), (1:16 mark).